[KOH-lair] (n. f.) Medieval folks didn't quite have everything figured out.

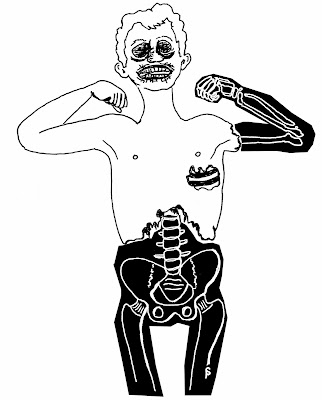

There were the open sewers that brought on disease but also common belief that redheads were automatically hot-tempered because of excessive hot & dry humours. The latter were quantifiable things, then. Ancient physiologists counted four humours, one of which was called choler—from the French word colère.

It was characterized by excessive yellow bile or choler (hence the word choleric) and led to extreme anger.

Word Goggles

corps — BODY

[korh] (n. m.) Paris has done some strange things with its corpses.

In Roman times, the dead were buried in the suburbs but, in the 10th century, Christians decided they preferred their dead nearby and cemeteries were opened. Two hundred years later, a central burial ground was opened for the poorer Parisians, a dump site for corpses without caskets. Problem was, all that decaying meat was threatening the city's water supply, which mostly came from wells. This went on merrily until 1786 when the city decided to exhume all those corpses and transfer them to underground tunnels once used for mining: the catacombs were born.

The English word corpse is just a breath away from the French word corps, which means body—of which there are an estimated six million underneath Paris. In French, the word is pronounced with the ps lobbed off, closer to the the Old French word cors, less like the latin source corpus.

The English word corpse is just a breath away from the French word corps, which means body—of which there are an estimated six million underneath Paris. In French, the word is pronounced with the ps lobbed off, closer to the the Old French word cors, less like the latin source corpus.

orner — DECORATE

[ohr-NEH] (v.) There's an Ethiopian tale about a fox who lost his tail in a trap.

At first, his shame keeps him from visiting fellow foxes but soon he comes up with a plan: he convenes all the area foxes and proposes that they all rid themselves of the "burdensome" appendage. "It's easier for dogs to catch us with these tails and they're in the way when we want to sit down," points out the fox. "That is all very well," responds one of the older foxes, "but I do not think you would have us dispense of our chief ornament if you had not lost it yourself."

The word ornament comes from the French verb orner which means to decorate and that's obviously not all a fox tail does.

At first, his shame keeps him from visiting fellow foxes but soon he comes up with a plan: he convenes all the area foxes and proposes that they all rid themselves of the "burdensome" appendage. "It's easier for dogs to catch us with these tails and they're in the way when we want to sit down," points out the fox. "That is all very well," responds one of the older foxes, "but I do not think you would have us dispense of our chief ornament if you had not lost it yourself."

The word ornament comes from the French verb orner which means to decorate and that's obviously not all a fox tail does.

patrie — PATRIOTIC LAND

In fact, it was often used in England as a term of ridicule to mean "loyal and disinterested supporter of one's country." What is even more amusing, as journalist Oriana Fallaci points out, is that while Americans are so fond of patriotic, patriot and patriotism, lack the root noun and are content to express the idea of patria (the proper noun that's never used) by cumbersome compounds such as homeland.

The French? Oh yeah, that have a noun for that: patrie.

inquiétitude — WORRY

[uhn-KEE-ETT-ee-tewd] (n. f.) "Be quiet! Quiet down! Quiet please. He was a quiet guy, a little too quiet... On a quiet street... She lived a quiet life... Before the hold-up, the criminal had remained quiet for years... The kid had a quiet conscience." Quiet is one of those English words used in myriad ways, to express something a little different every time, a lovely feature of this pliable language. Of course, quiet comes from the French word quiéte, which is the sort of word you can easily alter with suffixes and prefixes. Inquiéte means she is worried. But if you add the suffix -itude, which is the French equivalent of -ness (think of attitude, borrowed French for aptness), you get the noun inquiétitude (un-quiet-ness) which means worry.

BONUS: A commonly used American colloquialism is no problem, or for the Terminator no problemo. The French equivalent of this is t'inquiétes [tuhn-KEE-ETT]. It's short for ne t'inquiéte pas.

naitre — TO BE BORN

[NAY-trr] (v.) Calling someone a San Francisco liberal may be considered insulting in politics, but locals are very proud if they can call themselves true San Francisco natives. But to do that, you have to actually been born within its 47 square miles. The world native comes from the French natif which means born in. Think of the Bible's nativity scene. The verb associated with the noun is naitre, which means to be born. Actually, English speakers already use a conjugated—accented even—form of naitre for formal occasions. That's right. When you write Michelle Obama née Robinson to indicate her maiden name fancily, you're using the French for was born. The word nation also comes from naitre. So baseball's National League means "League of the place from which they were born" which, really, is much less specific then the good 'ol American League.

incendie — FIRE

[enh-so(n)-DEE] (n. m.) When someone writes an incendiary report it does not means they're going to use the paper and set something on fire with it, although, if they followed the word to the letter, that's exactly what they're letting on. The word actually comes from the Latin incendiarius which means to set on fire. The French, in their inflexibility with language, stuck with the Latin and still use the word incendie to mean a fire (as opposed to just the element of fire.)

ombre — SHADOW

[ohm-BRR] (n. f.) In the classic 1850 book The Scarlet Letter, there's a vivid description of the adulteress Hester Prynne during a meeting with the minister, Arthur Dimmesdale, who aids her:

Throwing eyes anxiously in the direction of the voice, he indistinctly beheld a form under the trees clad in garments so somber and so little relieved from the gray twilight into which the clouded sky and the heavy foliage had darkened the noontide that he knew not whether it were a woman or a shadow.

If it sounds as though her somber garments are made of shadows, it's not by chance. Somber comes from the French word sombre, meaning obscure or melancholy. But the s- is very telling. It's a shortening of the Latin prefix sub which means under (think of the subcontractor who works on your home). That means that sombre is really sub-ombre and ombre is French for shadow which makes a lot of sense if you think of being somber as being under (emotional) shadows.

BONUS: What is it about that weird American-English tug-of-war over certain word spellings? Why is it theatre in the U.K. and theater in the U.S.? Well, it's just that the English, in an effort to remain true to roots, tend to stick with the French spelling of those words. Americans, meanwhile, try to spell things more closely to the way they sound phonetically. That's why somber is spelled the way it and not -re at the end, because it is pronounced like that. Like they say: KISS, keep it simple, stupid.

marquise — MARQUEE

[mahr-KEEZ] (n. f.) The pop star is upset and pouting in her dressing room. Stuff was broken and her entourage's gotten an earful. It all started when she got to the venue and her name on the marquee was next to the opening act's, not on top of it. This is one pop star who wants to be treated like a monarch and it's fitting in a way: see, the term marquee was gleaned from the French marquise, a noblewoman. It all goes back to the 17th century when an officer's tent in a French military encampment was distinguished by having a linen canopy placed over it, indicating a place suitable for a marquis. They called that canopy a marquise. Come the early 1900s when Americans wanted to name those fancy canopies in front of a hotel, or theater. They grabbed the French marquise, mistakenly thought the s at the end made it plural, lobbed that off, and called it a marquee.

siège — SEAT

[SEE-ehj] (n. m.) The surest way to conquer a fortress is to take a seat. If the enemy's feeling all cozy in their keep, behind their moat, all your army does is just wait it out. Starve them by seating in camps around the castle, depriving them of supplies or communication. This is called a siege and it was named after a siège, the French word for a seat. The folklore surrounding King Arthur's Round Table makes use of the French word in its original meaning. The table had twelve seats but one was left empty for a knight who would achieve the Grail. They called it Siege Perilous. Some say it was Galahad who took the seat with the French moniker, others say it was Percival. But that's got nothing to do with anything.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)