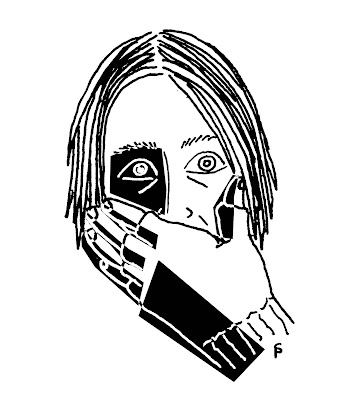

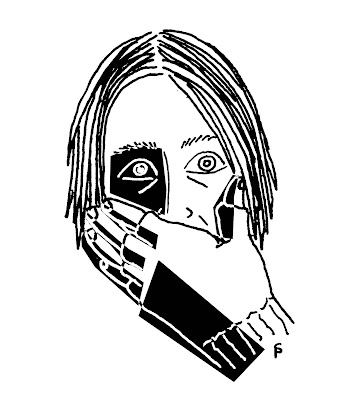

[MOO-fleh] (n. f.) To muffle a kitchen fire the housewife throws a towel on it, smothering it. To muffle a scream the murderer puts pillow on his victim's head. To muffle is to wrap something to conceal or protect. Its French origin is the moufle, an item of winter clothing meant to conceal or protect only the hands: a mitten. Okay but where does that leave us with mitten which doesn't resemble moufle? The word was borrowed phonetically from the French mitaine (pronounced exactly the same way) but with some confusion: that's the word for fingerless glove. Go figure.

[MOO-fleh] (n. f.) To muffle a kitchen fire the housewife throws a towel on it, smothering it. To muffle a scream the murderer puts pillow on his victim's head. To muffle is to wrap something to conceal or protect. Its French origin is the moufle, an item of winter clothing meant to conceal or protect only the hands: a mitten. Okay but where does that leave us with mitten which doesn't resemble moufle? The word was borrowed phonetically from the French mitaine (pronounced exactly the same way) but with some confusion: that's the word for fingerless glove. Go figure. moufle — MITTEN

[MOO-fleh] (n. f.) To muffle a kitchen fire the housewife throws a towel on it, smothering it. To muffle a scream the murderer puts pillow on his victim's head. To muffle is to wrap something to conceal or protect. Its French origin is the moufle, an item of winter clothing meant to conceal or protect only the hands: a mitten. Okay but where does that leave us with mitten which doesn't resemble moufle? The word was borrowed phonetically from the French mitaine (pronounced exactly the same way) but with some confusion: that's the word for fingerless glove. Go figure.

[MOO-fleh] (n. f.) To muffle a kitchen fire the housewife throws a towel on it, smothering it. To muffle a scream the murderer puts pillow on his victim's head. To muffle is to wrap something to conceal or protect. Its French origin is the moufle, an item of winter clothing meant to conceal or protect only the hands: a mitten. Okay but where does that leave us with mitten which doesn't resemble moufle? The word was borrowed phonetically from the French mitaine (pronounced exactly the same way) but with some confusion: that's the word for fingerless glove. Go figure. travaille — WORK

[TRAH-vah-y(e)] (n. m.) Travel in the Middle Ages was real work: slow, hard, uncomfortable and dangerous. Pot holes existed then because peasants would borrow cobblestones from roads to patch up their houses. Going 55 mph? It would take two days by horse to cover 55 miles. Forget about travelling at night, lest you got robbed. Most people never traveled more than 10 miles away from their birthplace, their whole life. Travel was such a laborious endeavor the Middle English speakers took the French word for work, travaille, to describe it. Knowing this, bilinguists might have fun calling the travelling salesman, threading miles door-to-door to sell a few wares, a travailleur traveler, a working traveler.

baraque — SHABBY HOUSE

[BAH-rha-KK] (n. f.) In the late 18th century, a young Napoleon was given command of the French forces in Italy. He gave them a speech in which he acknowledged their sacrifices. "Soldiers, you are naked, ill fed," he said, "You have made (...) forced marches without shoes, camped without brandy and often without bread." He should have mentioned the shoddy barracks soldiers often slept it, these musty, provisory huts they put together for camps. The French word baraque, technically still means temporary constructions but less in the military realm and, rather, refers to a building that won't last long because it's flimsy and poorly made.

gentil — NICE

[chj-anh-TEE] (a.) In formal speech, a genteel person has the qualities of a gentleman, a person of noble birth. The word is an anglicized version of the French gentil, which means nice. The British did this often; in order to aid pronunciation, they simplify the spelling of borrowed words. "Wait, the last syllable of gentil is pronounced -tee with a silent L? Nonsense, we'll just spell it with two Es and speak that L too! Genteel: that's much better." Within a century, genteel was squeezed out of common usage in favor of gentle (think of the theater/theatre debate). But it wasn't just adjective that was borrowed: gentleman is a cognate of the French gentilhomme, a simple switch: gentle for gentil and man for homme.

So, you see, a true gentleman would be incapable of insulting a woman, not only because of his noble birth but because he's a nice man.

cabriolet — CAB

[KAH-bree-oh-leyh] (n. m.) Cabriolets certainly are jumpy roadsters. And it makes sense because the cars are named after the 16th Century French verb cabrioler, which means "to leap or jump in the air like a goat." That's because an old French word for a young goat is cabri. So, picture a goat and it makes perfect sense they'd name the light horse-drawn carriage of the 1820s cabriolets. The term was extended to automobiles you hire to make short leaps about town, also known as taxicabs.

But what about taxi, you might wonder? Also from French: it's short for taximeter, which was used in London starting at the turn of the 20th Century and it's the anglicized version of taximètre. As in "tax by the meter." That's right, not taxiyard.

morceau — MORSEL

[mohr-SO] (n. m.) A strange case of shifting spellings, or not in English's case. Going way back, the Latin morsellum means "a small piece" and is made up of morsum (piece) and the diminutive -ellus. To get horribly specific about what kind of piece this is, it's good to know the word is derived from mordeo, or "to bite." Right away, the French had the good sense to ablate the word from morsellum to morsel, which is where the English left things.

During the Middle Ages, the French went through a period of systematically (that is, with a semblance of consistency) altering the spelling of Latin words they borrowed. One of these so-called Latin rules as they are called in Auguste Brachet's 1868 Dictionnaire Etymologique is that the s before a vowel often became a c. Hence, the Latin salsa became sauce and morsel begat morcel. Another Latin rule was that long vowel sounds should be shortened and the natural way of doing so was to slide down the vowel ladder which, both phonetically and alphabetically, goes a, e, i, o, u. (Brachet even points out that a starts at the base of the larynx while u expires on the lips, a natural order.) So the -el sounds often become an o sound and agnellus became agneau (lamb) and morcel became morceau.

remords — REMORSE

[REUH-mohr] (n. m.) We've gone at length on the history of morsel (see entry) and we know that the word is derived from the Latin mordus (in French simply mord) which means to bite. See, it's a poetic thought here that pressed remorse into usage. It's the feeling you get when something comes back to bit you, in little nibbles eating at your tranquility.

jetter — TO THROW AWAY

[jhe-TEH] (v.) When one is on a sinking ship (a literal one), it behooves one to throw things overboard in an effort to buy some added buoyancy and a little time. Once sunk, a ship will often also spill its load. As all this washes ashore or ends up on the ocean floor it can be divided into flotsam and jetsam. The difference is of great interest to Marine Insurance writers who consider things that floated off (flotsam) to be a free-for-all. However, things that were thrown off purposefully—or jettisoned—are considered the boat owner's property and can be reclaimed. These are called jetsam, a word derived from the French jetter, which means to throw away.

guerre — WAR

[gh-AIR] (n. f.) The 10th century Normans, those conquesting descendants of Vikings conquerors (the apple doesn't fall far from the tree...), were the first to take early French and start making it sound like what English is today. While the rest of France was speaking Françoys, the Norman were altering the pronunciation of words and taking those with them to vanquished England.

It's fitting to consider the French word guerre. While most of the country was pronouncing that "gh-AIR" with a hard G, the Normans in their province of Normandy saw that "gue-" and thought it sounded more like "gweh" to them. That Norman accent was also responsible for transforming the French surname "Guillaume" into "William." The rest was just a process of simplification: from guerre to "gwerre" to "werre" and finally war.

jaune — YELLOW

[(d)JOAN] (n. m.) You know you've got issues if your ears are turning red from guilt, your face is green with envy and you've got jaundiced eyes. The latter is thought to mean that you have a prejudiced view and it's the only one of these symptoms of real medical concern. Jaundice occurs in people that have an increase in bilirubin, a yellowish compound found in urine and bile, in the extracellular fluids. It gives the afflicted a yellow tint to the face and, more obviously, the eyes. Jaundice comes from the phonetically similar French word jaunisse, which means yellowness, and its cousin jaune, which means yellow.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)